The Distortion of UN Resolution 2758 and Limits on Taiwan’s Access to the United Nations

Yet, in passing the resolution in 1971, the countries solely intended to grant the seat occupied by the Republic of China in the General Assembly and the Security Council to the PRC. This is reflected in the official historic record and meeting minutes as well as in the resolutions raised at the time for the General Assembly’s consideration.

The PRC understood then that the resolution did not contain the Taiwan conclusions it wanted. Prime Minister Zhou Enlai noted that, if Resolution 2758 passed, “the status of Taiwan is not yet decided.” Beijing, through its proxies at the UN, expressed its unwillingness to join the organization if it allowed “‘two Chinas,’ ‘one China, one Taiwan,’ or ‘the status of Taiwan remaining to be determined.’” However, given that Beijing did not enjoy the same level of international influence then as it does today, it did not reject the resolution when it passed. Instead, PRC officials assumed the “China” seat and only later began to leverage their position to promote Beijing’s stance on Taiwan at the UN level.

The PRC’s efforts to rewrite Taiwan’s status at the UN ramped up in the 1990s and early 2000s at the same time as the island’s democratization. The PRC has since worked to “internationalize” its “One China” Principle and to conflate it with UN Resolution 2758, a revisionist shift from the original intent of the document.

Beijing has managed to further institutionalize and normalize its stance on Taiwan within the UN by signing secret agreements with UN bodies, restricting Taiwan’s access to the UN and its facilities, and embedding PRC nationals across various levels of UN staff. The UN and its specialized agencies have not made the texts of these agreements, such as that of the 2005 memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the PRC and the World Health Organization, available to the public or to any entity beyond the main signatories, though leaked guidance memos provide insights into the scope of the MOU’s content (See Appendix B).

The PRC has likewise sought to force its views on nomenclature relating to Taiwan within the UN. This includes withholding UN accreditation from NGOs and civil society groups that do not refer to Taiwan as a part of the PRC in their organizational materials or on their websites. Recently, it has come to light that the PRC and its representatives have altered historic UN documents to change references of “Taiwan” to “Taiwan, Province of China.” (Examples are presented in a case study.)

These developments have played out alongside marked shifts in the guidance of the UN Office of Legal Affairs on Taiwan, where it only 15 years ago cited an ambiguous and undefined “One China” policy, but now reiterates the PRC position on Taiwan.

The PRC has likewise used UN Resolution 2758 and bilateral normalization agreements with other member states to falsely claim that its “One China” Principle is a universally accepted norm. It has also ensured that a plurality of countries back its views at the UN level and will cast votes alongside it—particularly on issues of Taiwan’s participation—and it reinforces this support through economic pressure on governments.

The PRC’s efforts to constrain Taiwan at the UN have broader implications for international governance, as it shows a prioritization of one member state’s national interests over the global community’s—as exemplified by Taiwan’s damaging exclusion from global health debates during the coronavirus pandemic. The United States opposes the PRC’s attempts to redefine UN Resolution 2758 and has pushed back against UN statements claiming that Taiwan is a province of the PRC, including issuing a 2007 “non-paper” asserting its position that Taiwan’s status is not yet determined. The PRC has recently attempted to use its narrative of the “One China” Principle as embedded in UN Resolution 2758 to call into question the legitimacy of longstanding US policy on Taiwan—including the Taiwan Relations Act, which is US law.

Read the Case Studies

Click here to jump down this page and explore the case studies from The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), The Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM), and The International Telecommunications Union (ITU).

The below excerpt has been adapted from the full report. The full report can be found exclusively in PDF format, at the bottom of this page or here.

October 25, 2021 marked the 50th anniversary of the passing of United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Resolution 2758. In the half century that has passed, the global landscape has shifted markedly from that day in 1971 when the People’s Republic of China (PRC) formally replaced the Republic of China (ROC) as the holder of the “China” seat in the UNGA and the UN Security Council (UNSC).

Of the two main affected parties, the PRC has since enjoyed unprecedented economic growth, which has simultaneously fueled its military modernization and enabled the expansion of its international presence and influence, including in key intergovernmental organizations. For its part, Taiwan has transitioned from an authoritarian government under Chiang Kai-Shek to a thriving democracy of 23.5 million and become a key node in global technology supply chains. It has a robust civil society with world-class expertise on an array of transnational issues, from public health and climate change to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.

Yet, despite these accomplishments, Taiwan officials and representatives of its nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are often excluded from attending and participating in discussions on these pressing topics in international fora, including those led by the UN and its affiliated organizations. This is in spite of the fact that, for the past decade, Taiwan has prioritized participating in targeted UN specialized agencies, aiming to make functional contributions as a responsible international stakeholder.2

The primary reason for Taiwan’s exclusion is the PRC and its relentless efforts to distort the original text of UN Resolution 2758 in ways that construe it as equivalent to its “One China” Principle, which states that “there is only one China in the world, Taiwan is a part of China and the government of the PRC is the sole legal government representing the whole of China.”3Beijing alleges that the UN has adopted its position that Taiwan is a part of the PRC and it has worked to insinuate its political priorities at the UN level. It has allowed and tolerated the inclusion of Taiwan when it is governed by the Kuomintang (KMT) party—achieved under a vague understanding between the KMT and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that both sides of the Taiwan Strait belong to “One China”—while staunchly blocking Taiwan when it is governed by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the inauguration of President Tsai Ing-wen from the DPP in May 2016, Taiwan has yet again been prevented from participating in UN and UN-affiliated organizations.

The PRC’s ability to do so can be attributed to its disproportionate influence within the UN system—attained through a variety of means such as specialized funding schemes, the signing of memoranda of understandings (MOUs), and embedding PRC nationals across all levels of UN staff as well as outside it. This also includes using a combination of carrots and sticks to convince other countries, predominantly those in the Global South, to vote alongside China in support of its interests on the UNGA floor.

The PRC has over time seen success in normalizing its stance on Taiwan within UN institutions and in getting a plurality of countries to back its views—which then bolsters its argument that there is an international consensus on its claim to the island. However, UN Resolution 2758 does not substantiate this and is succinct in its language.

Crucially, UN Resolution 2758 does not include the words “Republic of China” or “Taiwan”—it merely alludes to the former vacating its UN seat. Accordingly, it does not present an institutional position on the status of Taiwan, even though the PRC claims it does—it solely states that the PRC will, from that day forth, represent “China” at the UN.4

This report first explores the geopolitical backdrop to UN Resolution 2758 and reviews historical UN documents and meeting minutes to demonstrate that member states’ original intent for the resolution was solely to determine the holder of the “China” seat at the UN. It then examines how the PRC has worked over the years to drive a new narrative around the resolution by conflating it with the “One China” Principle. It then explores the nature and extent of PRC efforts to restrict Taiwan at the UN and its related organizations, assessing the broader implications of PRC influence within the UN system. The conclusion sets out policy recommendations on how to preserve space for Taiwan’s meaningful participation in the UN.

Full Text of UN Resolution 2758

THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY

Recalling the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

Considering the restoration of the lawful rights of the People’s Republic of China is essential both for the protection of the Charter of the United Nations and for the cause that the United Nations must serve under the Charter.

Recognizing that the representatives of the Government of the People’s Republic of China are the only lawful representatives of China to the United Nations and that the People’s Republic of China is one of the five permanent members of the Security Council.

Decides to restore all its rights to the People’s Republic of China and to recognize the representatives of its Government as the only legitimate representatives of China to the United Nations, and to expel forthwith the representatives of Chiang Kai-shek from the place which they unlawfully occupy at the United Nations and in all the organizations related to it.5

China and Taiwan at the UN Today

As shown above, over the past five decades, the PRC has systematically reframed the narrative around UN Resolution 2758. It has gone from keeping the resolution separate from its claims to Taiwan to asserting that the resolution substantiates its “One China” Principle.

Concurrently, Beijing has worked to embed its position on Taiwan within the UN and its affiliated agencies to justify the exclusion of Taiwan from all UN activities. These efforts have been more public and prominent when the DPP is in power in Taiwan, but have nonetheless continued when the KMT is in office, and go hand in hand with the broader trend of deepening Chinese influence at the UN. In 2021, which marked the 50th anniversary of the passing of UN Resolution 2758, steps by Chinese officials and representatives to consolidate PRC claims to Taiwan at the UN have ramped up, reaching an all-time high.

The extent of PRC efforts to codify the “One China” Principle into the UN system is pervasive—no issue item, memo, or note is too small or insignificant for Beijing and its proxies to overlook—and their influence and reach is wide-ranging. While the magnitude of these efforts is impossible to fully capture, largely due to the opaqueness of the UN system, the examples below drawn from publicly available, open-source information show how Taiwan is being systematically recast as a province of China:

Limiting Taiwanese Access to UN and UN Facilities

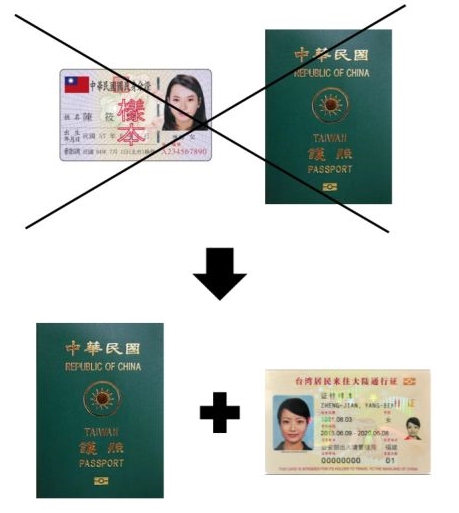

As discussed above, ROC passport holders continue to face restrictions accessing UN buildings and offices. This has become more pervasive during the Tsai administration, though restrictions have been applied inconsistently. In one instance in June 2017, a Taiwan professor, Liuhuang Li-chuan, and her students were denied entry into the public gallery of UN human rights office in Geneva after being told that their international student identification cards were not an acceptable form of documentation and that only documents issued by the PRC would be allowed. The professor says she was shown a document of internal guidelines provided to UN staff checking in visitors.66 Figure 3 shows a mockup of the internal UN documents seen by Liuhuang when she and her students were denied entry to the UN facilities, which revealed that a combination of ROC national identity card and ROC passport was deemed unacceptable (top) while a ROC passport with a Mainland Travel Permit for Taiwan Residents (bottom) was permitted. 67

Figure 3. Mock-up of Internal UN Documents Regarding the Entry of ROC Citizens in UN Facilities in Geneva.68

In another case in October 2018, a journalist was blocked from entering the UN headquarters building, despite having both an ROC passport and a Mainland Travel Permit for Taiwan Residents, because he did not have a PRC passport.69 Others affected include Taiwan scientists, subject-matter experts, human-rights activists, and other members of civil society who were invited to take part in UN-affiliated events but were unable to step foot in UN compounds or who had their applications for online forums rejected.70

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken released a press statement in October 2021 that highlighted this issue, saying:

Members of civil society from around the world engage every day in activities at the UN, but Taiwan’s scientists, technical experts, business persons, artists, educators, students, human rights advocates, and others are blocked from entry and participating in these activities simply because of the passports they hold.71

Nomenclature

How Taiwan is referenced at the UN and in UN documents has been a pervasive issue, with the PRC working assiduously to insert language that identifies Taiwan as a “Province of China.” It likewise pressures NGOs seeking access to the UN to make the same adjustments in their organizational materials. The United States has expressed concerns about this. In November 2021, Erica Barks-Ruggles from the Department of State’s Bureau of International Affairs stated that there have been “efforts to change how Taiwan is referred to in UN documents” and that Washington will “continue to push back.”79 Earlier, in January 2020, Courtney Nemroff, the acting US representative to the United Nations Economic and Social Council, noted that “In 2010, the UN’s Office of Legal Affairs made it clear that the UN may not alter the nomenclature in documents submitted by UN member states” and that “[t]his principle, based on non-interference in official positions, equally applies to submissions by NGOs.”80

In the past few years, there have been numerous instances of the PRC preventing NGOs, civil society representatives, and even high schools, from accessing UN resources or attending UN-organized forums and events if Taiwan features on their websites or organization materials as “Taiwan,” as opposed to “Taiwan, Province of China.”81 Affected organizations that often do not want to become involved in geopolitical issues, are unaware of the nuances, or seek to avoid negative repercussions generally acquiesce to enable entry and access to UN-related organizations.82 (See the case study section.)

Further exacerbating the issue are the standards set forth by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), an “an independent, non-governmental international organization with a membership of 167 national standards bodies” that develops international standards, including on how countries are designated and “us[ing] United Nations sources to define the names of countries.”83 Taiwan has been designated as ISO 366, “Taiwan (Province of China)” since 1974, having made unsuccessful efforts to join in relevant discussions and to amend how it is named.84

The PRC’s objective appears to be to implant the “One China” Principle across all levels of the UN and its related organizations, and to establish an equivalency between it and UN Resolution 2758 so that this position becomes customary international law, or “international obligations arising from established international practices.”85 Notably, since its 2000 “One China” Principle white paper, the PRC has used a mutually reinforcing argument to claim the universality of its position on Taiwan. First, that since UN member states have subscribed to the “One China” Principle through diplomatic recognition of the PRC,86 this validates the “One China” Principle at the UN-level and in UN Resolution 2758. And second, the converse, that UN Resolution 2758, which was successfully passed by a plurality of UN member states, requires countries to agree to the “One China” Principle. Embedding its stance on Taiwan within UN organs seems to be the next layer and Beijing has already achieved headway on this front.

As mentioned above, the United States and its allies and partners successfully pushed back against UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon’s statement in 2007 that Taiwan is a province of China. Ban indicated that he “went too far” and the OLA agreed to drop “the unhelpful phrase.” That same year, Taiwan’s bid for UN membership was rejected, with the OLA noting that it based its decision on UN Resolution 2758, which it said “recognized the UN’s ‘One China’ policy [italics added]”—seemingly reverting to existing UN policy, with its “One China” policy first publicly referenced in 2003.87

While the UN’s “One China” policy has never been defined, there has been a marked shift in the OLA’s guidance on Taiwan—from citing a UN-wide “One China” policy to explicitly reiterating the PRC position on Taiwan. That shift prompted US official criticism during the Trump administration. In January 2020, Acting US Representative Nemroff stated that: “We note that we do not accept other aspects of OLA’s opinion, namely that General Assembly resolution 2758 means that the UN must consider Taiwan to be a province of China.”88 The PRC view, by contrast, was exemplified by Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Xie Feng in November 2021 when he said that the OLA:

in a number of legal opinions following the resolution, has also confirmed that “the United Nations considers ‘Taiwan’ as a province of China with no separate status,” and the ‘“authorities’ in ‘Taipei’ are not considered to enjoy any form of government status.”89

Leveraging UN Member States for Support of PRC Views

As noted, the PRC has gradually shifted the narrative on UN Resolution 2758 so that it is tied as closely as possible to its conceptualization of the “One China” Principle. Along with this effort, it has worked to convince other UN member states to fall in line with this position.

The PRC has used UN Resolution 2758 and its bilateral normalization agreements with UN member states to promote international acceptance of its “One China” Principle. It wields undue influence over smaller UN member states, particularly those that encompass the Group of 77 (G77), a coalition of developing countries generally of the Global South. Since the founding of the PRC, Beijing has successfully weaved an anti-colonial narrative, which has garnered the sympathy of the G77, including prior to its assumption of the “China” seat at the UN, and it has since received relatively consistent support from the group. These countries often repeat PRC talking points on the “One China” Principle and UN Resolution 2758 as well as vote alongside the PRC on motions in UN fora on allowing Taiwan’s participation, ensuring an effective voting bloc to deny the latter access.90

When G77 countries diverge from the PRC’s preference, they become targets of its economic pressure. There have been reports of Beijing using its loans to African countries as leverage to encourage African diplomats to align with PRC motions and sign on to PRC joint statements at the UN—with particular emphasis on opposing Taiwan’s WHO bids for observership. For those that are hesitant or object, Beijing allegedly threatens consequences by broaching the subject of outstanding debts.91

Case Studies: Compelling NGOs to Change References to “Taiwan” and Revising Historical UN Documents

There have been numerous media reports on the breadth of PRC influence at the UN, including how NGOs are being restricted from UN access and accreditation, particularly at the ECOSOC, if they do not comply with Beijing’s demands to reframe references of “Taiwan” to “Taiwan, Province of China” on their websites and publications.CS1 Yet, the extent of this pressure and the ways it is being applied is not fully appreciated. The PRC is increasingly threatening independent organizations with losing access to the UN if they do not adopt its preferred language regarding Taiwan. There are also instances of UN documents being revised to accommodate PRC preferences. These issues, when taken together, show a clear trend of privileging one member state’s interests over the UN’s stated commitment to partnering and sharing information with civil society.CS2

Below are examples of such changes and revisions. These examples showcase ways the PRC is using the UN and its affiliated agencies as a medium through which to pressure NGOs and to gain further leverage on Taiwan.

- 2For more details, see Bonnie Glaser, Taiwan’s Quest for Greater Participation in the International Community, Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 2013.

- 3The Taiwan Affairs Office and The Information Office of the State Council, White Paper—The One China Principle and the Taiwan Issue; Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Kingdom of Norway, February 21, 2000.

- 4Yu-Jie Chen, "Must Taiwan Remain Invisible for the Next 50 Years?" The Diplomat, October 25, 2021.

- 5American Institute in Taiwan, U.N. Resolution 2758 - Oct. 25 1971.

- 66Elson Tong, "Not just officials: Taiwan students blocked from visiting UN public gallery in Geneva," Hong Kong Free Press, June 15, 2017.

- 67Ibid.

- 68Ibid.

- 69Jennifer Creery, "Taiwan lodges protest with the United Nations for denying entry to Taiwanese reporter," Hong Kong Free Press, October 15, 2018.

- 70Jess Macy Yu, "Taiwan says shut out of U.N. climate talks due to China pressure," Reuters, November 14, 2017; Lu Yi-hsuan and William Hetherington, "Taiwanese shut out of UNESCO events," Taipei Times, December 7, 2020.

- 71US Department of State, Supporting Taiwan’s Participation in the UN System, October 26, 2021.

- 79Erica Barks-Ruggles, Personnel is Policy: UN Elections and US Leadership in International Organizations, statement before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Subcommittee on International Development, International Organizations and Global Corporate Social, November 18, 2021.

- 80United States Mission to the United Nations, Opening Remarks at a UN General Assembly Meeting for the UN Committee on Non-Governmental Organizations, January 20, 2020.

- 81Stu Woo, "China Makes Sure Everyone Writes Taiwan’s Name Just So—Even a Colorado High School," Wall Street Journal, September 10, 2021.

- 82Ibid.

- 83International Organization for Standardization, About Us, and What We Do, accessed March 11, 2022; Reuters, "Top Canada university says won’t call Taiwan part of China after complaint," July 7, 2020.

- 84Sean Lin, “Protests about ISO designation are to continue: Cabinet,” Taipei Times, November 8, 2019; Huang Tzu-ti, “Taiwan urged to address mislabeling by ISO as part of China,” Taiwan News, November 7, 2019.

- 85Cornell Law School: Legal Information Institute, Customary International Law, accessed December 15, 2021.

- 86Many countries maintain their own “One China” policies that can be distinct from the PRC’s “One China” Principle. For example, the United States and several of its allies and partners have “One China” policies that hold that Taiwan’s status is undetermined. For more, see Richard Bush, A One-China policy primer, Brookings Institution, March 2017.

- 87Representative Bill Sali, speaking on the United Nations Office of Legal Affairs rejecting Taiwan’s bid for membership, September 6, 2007, Congressional Record 153, pt. 17: 23860; Mazza and Schmitt, Righting a Wrong.

- 88United States Mission to the United Nations, Opening Remarks at a UN General Assembly Meeting for the UN Committee on Non-Governmental Organizations.

- 89Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, China-US Presidential Meeting: Setting Direction and Providing Impetus for Bilateral Relations— Transcript of Vice Foreign Minister Xie Feng’s Interview with the Press, November 16, 2021.

- 90U.N. GAOR, 62nd Sess., 3rd plen. mtg., U.N. Doc A/62/PV.3 (September 21, 2007); U.N. GAOR, 61st Sess., 2nd plen. mtg., U.N. Doc A/61/PV.2 (September 13, 2006); U.N. GAOR 59th Sess., 1st plen. mtg., U.N. Doc A/BUR/59/SR.2 (September 15, 2004).

- 91Africa Confidential, “Beijing uses its leverage,” October 22, 2021.

- CS1Stu Woo, “China Makes Sure Everyone Writes Taiwan’s Name Just So—Even a Colorado High School,” Wall Street Journal, September 10, 2021.

- CS2United Nations, The UN and Civil Society, accessed February 12, 2022.

Case Studies

Expand AllThe World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO):

WIPO is a specialized agency of the UN that serves as a “global forum for intellectual property (IP) services, policy, information and cooperation.”[CS3] During the 2020 Assemblies of the Member States of WIPO, the PRC delegation requested to suspend the discussion on Wikimedia Foundation’s application for observership to WIPO because the information available on Wikipedia—which is hosted by the Wikimedia Foundation—features content that purportedly “violated” the PRC’s “One China” Principle and UN Resolution 2758.[CS4]

Given that any member state can veto accreditation, the Wikimedia Foundation was blocked from acquiring observer status at WIPO in 2020 and again in 2021, despite submitting materials describing how Wikipedia works and how the foundation does not directly manage its authors and contributors.[CS5] The foundation has said that it plans to reapply for observer status in 2022 but that it understands “it will only be admitted by WIPO if China decides to lift its blockade.”[CS6]

Changes made to Assemblies of the Member States of WIPO: Sixty-First Series of Meetings (Geneva, September 21 to 25, 2020), General Report (highlights added)[CS7]

[CS3] World Intellectual Property Organization, Inside WIPO: What is WIPO?, accessed February 12, 2022.

[CS4] WIPO, Assemblies of the Member States of WIPO: Sixty-First Series of Meetings. A/61/10 (September 21–25, 2020).

[CS5] Wikimedia Foundation, “China blocks Wikimedia Foundation’s accreditation to World Intellectual Property Organization,” September 24, 2020; Wikimedia Foundation, “China again blocks Wikimedia Foundation’s accreditation to World Intellectual Property Organization,” October 5, 2021; and WIPO, Assemblies of the Member States of WIPO: Sixty-Second Series of Meetings. A/62/13 Prov (October 4–8, 2021).

[CS6] Wikimedia Foundation, “China again blocks Wikimedia Foundation’s accreditation to World Intellectual Property Organization,” October 5, 2021.

[CS7] Ibid.

The Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material (CPPNM)

The CPPNM, under the auspices of the International Atomic Energy Agency, holds an annual conference to review the implementation of the convention.[CS8] NGOs are allowed to participate as observers, but are “subject to the approval of the Parties [to the CPPNM]” and “participate as determined by the Parties.”[CS9]

In late December 2021, the PRC objected to the participation of five organizations, which were directed to correct “mistakes” in their publications that mention Taiwan or risk having their attendance blocked.[CS10] These organizations include the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) and the Stimson Center, a US think tank.

NTI and Stimson bowed to PRC pressure to avoid being barred from participation in UN conferences and losing access to the UN and its affiliated agencies, which are essential to their work. The demands demonstrate that PRC representatives have identified and targeted critical pressure points that can be applied to compel NGOs to comply or lose invaluable resources provided by access to the UN.

NTI made adjustments to its website’s “Taiwan” country page, which originally featured an image of the ROC flag, as well as text description of “losing mainland China to the Chinese Communist Party.”[CS11] Both have since been removed, while a sentence explaining Taiwan’s inclusion among country pages has been added.[CS12]

Changes made to Nuclear Threat Initiative website in 2021

In addition, the PRC complained that one of the Stimson Center’s reports on illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing contained “incorrect” references to Taiwan.[CS13] The Stimson Center made changes to the wording of the report to address PRC concerns. Box B shows the original text at the time of publication in November 2019 and the amended text that is now on the Stimson Center website. Of note, all sentences in which Taiwan was referenced alongside China have had the latter changed to “Mainland China,” as seen in the page 2 example.

Changes made to a 2020 Stimson Center report, “Shining a Light: The Need for Transparency across Distant Water Fishing”

[CS8] “Conference of the Parties to the Amendment to the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material 2022,” International Atomic Energy Agency, accessed February 12, 2022.

[CS9] Ibid.

[CS10] Private interview on February 3, 2022.

[CS11] “Taiwan,” Nuclear Threat Initiative, web-archived date: October 22, 2021.

[CS12] “Taiwan,” Nuclear Threat Initiative, accessed February 12, 2022.

[CS13] Private interview on February 3, 2022.

The International Telecommunications Union (ITU)

Perhaps most egregious cases are the ones in which UN personnel revised historical documents, replacing original mentions of “Taiwan” with “Taiwan, Province of China.” One such instance was found in a 2014 ITU report on disaster relief. Another example was found in a report of an Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) Study Group meeting in Geneva from November 2000.

Changes made to ITU Report on Disaster Relief Systems

Bottom: Current version on website, page 8.

Changes made to ITU ICT Study Group report

Bottom: Edited version, January 2021

Policy Recommendations

The United States should develop a strategy to push back more effectively against the PRC’s attempts to redefine UN Resolution 2758 as encompassing its “One China” Principle and against its broader pressure campaign against Taiwan’s participation at the United Nations. This should consist of the following elements.

- The United States should launch a major diplomatic effort to forge a group of like-minded countries willing to challenge the PRC’s interpretation of UN Resolution 2758. This group should write a letter to the UN secretary general expressing their opposition to Beijing’s attempt to distort the meaning of the resolution to block Taiwan’s participation in the UN.

- The United States and its allies should press the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), an independent NGO with a membership of 167 national standards bodies, to reverse its decision to use “Taiwan, Province of China.” The ISO usage has led many international organizations and multinational corporations to adopt the same lexicon.

- The United States and its allies should take steps to curb the PRC’s growing coercive and corrupting influence as well as its efforts to promote and legitimize its agenda across the UN system. In particular, there should be a sustained effort to lobby against the appointments and elections of PRC nationals to high positions in UN agencies. The United States and its allies should take additional steps to safeguard the secrecy of national voting for leadership positions of UN bodies.

- The US Mission to the UN should request that the full text of all MOUs and other agreements that the PRC has signed with the UN Secretariat and with UN funds and programs—including those concerning Taiwan— should be made public.

- The United States should reassess its approach to voting blocs in the UN voting and branch beyond the support of its traditional allies and partners, developing strategies and outreach to UN member states on an issue-by-issue basis, including those that touch on Taiwan’s meaningful participation.

- The United States should publicly emphasize the differences between its “One China” policy and Beijing’s “One China” Principle. It should encourage other countries that have “One China” policies that differ from the PRC’s “One China” Principle to do the same. US officials should make clear that the United States acknowledges the Chinese position that Taiwan is part of China but does not accept PRC claims to sovereignty over Taiwan.

- Building on existing congressional interest,111 the Department of State should leverage its membership on the NGO Committee, the Economic and Social Council, the Human Rights Council, and in other relevant fora to highlight and counter PRC efforts to restrict UN access and participation by otherwise qualified NGOs that refer to Taiwan in their communications without adding “Province of China,” that have offices in Taiwan, or that partner with Taiwanese organizations.

- 111The America COMPETES Act of 2022, H.R. 4521, 117th Cong. § 30210 (as passed by the House of Representatives, February 4, 2022).

About the Authors

Jessica Drun is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council's Global China Hub.

Bonnie Glaser is director of the Asia Program at the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the officials and experts interviewed in the preparation of this report. In addition, we would like to thank the GMF Communications and Publications teams for their input and assistance in the production of the report.

This report was made possible by the generous support of Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office in the United States (TECRO). All opinions expressed herein should be understood to be solely those of the authors. As a non-partisan and independent research institution, The German Marshall Fund of the United States is committed to research integrity and transparency.